Excellency and Dear brother President Thabo Mbeki,

Beloved Sister Zanele Mbeki,

Distinguished Participants:

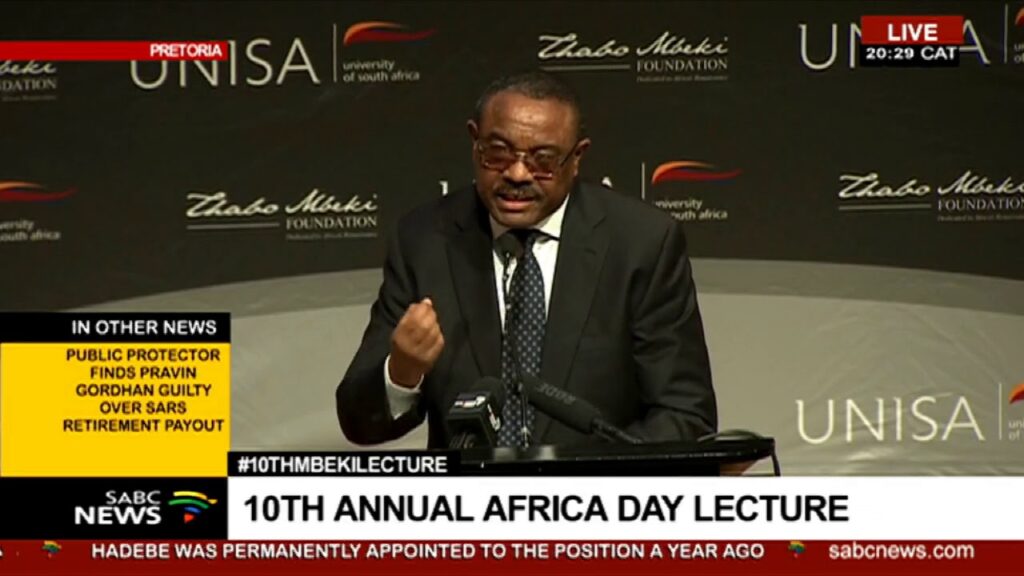

I am truly excited to speak to distinguished scholars, politicians, diplomats, civil society groups and above all to our student community on Africa’s burning topic – National Question and It’s implication on Peace and Democracy. I am honored to be part of the 10th year celebration of the Thabo Mbeki Annual Africa Day Lecture Series.

President Mbeki, congratulations! Thank you for bringing this family together once again. You are an inspiration.

Nothing gives me more pleasure than to be here with you today. Those of you who follow Ethiopian politics would know that with the launching of sweeping reform in my own country and the challenges ahead, this is not an invitation I take lightly.

If we need to get out of the nationalist tensions that most of us find ourselves in today, we need to think at Africa level. Not at ethnic level. Not at regional level. Not even at federal or national level. But at Africa level.

That is why I did not hesitate to come when brother Mbeki told me of what he had in his visionary mind. But I would like to put on the record that I also came out of duty – because I believe we owe it to our children that we get Africa in order before we pass it down to them.

So many leaders that have come before us have laid the foundation for us to build on. We no longer have to fight the liberation struggle. They have fought that for us. Even though still weak we can also say with certain humility that they have built really important institutions. We can improve them, but in most cases we will not have to create them from scratch.

And almost 66 years after our predecessors sat in our capital Addis Ababa and forged the African Union, then known as Organization of African Unity, we are finally talking about continental economic integration in which we can trade amongst ourselves free of tariffs.

We are also coming up with a new reality in which all African children, mine and Mbeki’s, Kenyatta’s and Akufo-Addo’s, Kagame’s and Buhari’s, Ramaphosa’s and el-Sisi’s will hold one African passport. It has been slow, but we have come so far.

On the other hand, as we are trying to bring the continent together we also have to deal with ethno-nationalist forces pulling in the opposite direction. Most of us present here today may look at a strongly-linked Africa.

Others look at even smaller countries – perhaps as many countries as languages. Is it even politically palpable? No.

But at the same time, can we think of an economically and politically integrated Africa without first dealing with our national questions, which in most cases are legitimate questions? I don’t think so.

Our African dictums teach us that our families are the smallest forms of government. Families. Clans. Ethnicities. Nations. Nationalities. Countries. All of these constitute Africa. All of these need to be recognized as such. As living, legitimate entities. And their questions need to be addressed to the best of each of our countries’ abilities. Otherwise, our continental projects will be doomed to fail before we embark on them, our pan-African dreams will remain mirages, and Africa will be a beautiful bag with a hole in it.

But that is not what we intend to leave behind us, is it? The Africa we all want to leave behind is peaceful, democratic and prosperous. The Africa we all want to leave behind is one in which nobody is left behind. Nobody, no family, no clan, no ethnicity, no region or nation, regardless of their size or location, should feel relegated to a second or third class citizenship. Our fathers and mothers have paid too heavy a price for any African to languish in that tiered citizenship anymore. So what must we do?

That, sisters and brothers, is the central theme of what I am about to speak to you today. The national question and its implication on peace and democracy – how do we reconcile these as we go forward?

But before I delve into substantive issues, let me review very briefly what political scientists and politicians are telling us about Nations, Nationalities, Nationalism, Ethnicity, Nation States, and Multi-National States etc.

According to Ernest Renan (Renan, 1981, 81-106) Nation is a distinctive historical consciousness whose grounds are to be found in the common past, and the will to live together in the present. Ethnic origin, language, religion, and territory need not be decisive factor.

Max Weber (Weber, 1994, 21-5) on his part underlined the political dimension of the national phenomenon. He argues that the concept of the nation is not empirically definable. For him National identity flows from the feeling of solidarity in relation to other groups and national solidarity from the memory of a common political fate. The National feeling is definable only in relation to the inclination towards the one autonomous state.

From far left ideologues and politicians like Otto Bauer (1881-1938) an Austro-Marxist and a social Democrat, and Stalin, who from within the communist movement gave the longest abiding and eclectic definition of the nation, is summarized as follows.

For Bauer, certain characteristics make up the nation only in the context of interdependence. The essential element is common history. In various nations these elements occur in various combinations. According to him, the nation emerged from the community of origins and the community of cultures. Language is a distinctive feature of a nation only if it produces the community of culture. He defines the nation as the totality of peoples united by a common fate.

Stalin on his part said that the nation is a historically formed stable community of people based on the community of language, territory, economic life and character, which is manifested in the community of culture. For Stalin, only all these elements make up a nation.

A Slovenian scholar, Kardelj (1967, 28) has defined nations as emerging together with capitalist production. Thus, he said, a nation is a specific people’s community which resulted from the social division of labor in capitalism or at its level of development of the means of production when the quantity of the surplus of social labor began to be transformed into a new quality of the social integration on a higher level. That is on a compact national territory within a framework of a common language and close ethnic and cultural similarities.

Stalin’s definition of the nation and that of Kardelj’s are criticised by other scholars and politicians that they did not grasp that the nation is a political phenomenon expressing political interests of a community. Besides, in his definition Stalin does not mention the level of economic development, a prerequisite for the formation of nations.

When we come to Western political science a number of scholars have tried to define the nation following the Western tradition. Amongst them Carl Deutch (Deutch, 1966) explains nations and nationalism by the development of the communications revolution in the modernization process, which enables us to experience history as a common history.

Hetcher (Hetcher, 1975) elaborates that in case of the inequality among a country’s regions, the result of the modernization may be internal colonialism in which the central region becomes dominant, while the peripheral regions become inferior which calls for nationalities in these regions to pose the national question.

A Norwegian political scientist, Stein Rokkan (Rokkan, 1982, 1983), similarly warns that the relation between the centre and the peripheral becomes a potential source of territorial conflicts and nationalism when there is no harmony among cultural, economic and political roles.

An American political scientist Walker Connor (Hutchinson, 1994, 37) said that what matters is not what is, but what belief is. According to him a nation is an ethnic group aware of its distinctiveness and a self-defining group. Similarly Hugh Seton-Watson (Seton-Waston, 1980, 29) like Connor, is a proponent of the self- defining hypothesis.

According to him a nation is a community united through a feeling of solidarity, although various factors may play a part in the process of nation building.

Many other scholars both from the West and East or from Marxism and liberalism could be cited but the whole review might lead one to think that the advent of nations has its objective and subjective presumptions, that in the last instance it is about the feeling of the existence of common interest. That interest is defined as a political goal which could be from interest protection within multinational setting, to the establishment of the nation state.

Also, the nation is undoubtedly a historical phenomenon linked with modernization. The integration of a nation into a nation state is the end of the process with which a community turns into a nation. It is called nation building.

Most often, the nation is built on the common, real or perceived ethnic origin. However, what essentially distinguishes a nation from an ethnic group is its political dimension, which is most obvious in a national political movement.

Therefore, based on the research in Nigeria, Ayokhai and Peter defined the national question as a question consisting of the political mobilisation and struggles by dissatisfied and aggrieved ethnic groups to redress and exact a more just and equitable accommodation from the state.

To me the national question is a term used for a variety of issues related to national development, which is how to structure the nation in order to accommodate groups and guarantee access to political power and equitable distribution of resources for the common good.

Therefore the national question focuses on the competition and conflict between and among different ethnic groups or nations and nationalities to control the political power and resources.

In Ethiopia and in Nigeria for example, the background to the national question is the perceived and real domination of political elites of some ethnic groups by the other, due to the historical and structural nature of the nation, such us the centre-periphery relations.

Let me give you a bird’s eye view to the political history of Ethiopia so that you can better conceive and contribute to the solutions of its daunting current challenges due to the national question.

We Ethiopians trace our history to more than 4500 years back. Historical evidence show that the Ethiopian (Abyssinian) empire has existed at least for 3000 years on this planet. Archaeological findings are surfacing evidence that the Da’mot civilisation and Axumite civilisation existed for at least two millennia.

The legendary House of Solomon that was presumed to have been founded around 900 BC has continued up to the time of Emperor Haileselassie II.

Chronicles of kings and queens, stele and stone inscriptions etc, testify that there were more varied and smaller ethnic groups living in the north eastern Africa region (now called Ethiopia, Eritrea, Somalia, Djibouti and the Sudan) than there are today.

Inter-clan and inter-ethnic wars have been the phenomena of the major part of the history of Ethiopia. However, a lot of integration has taken place since.

During the 2nd half of the 18th century and the 1st half of the 19th century, regional warlords have taken precedence over the central government of the empire.

Regional lords that referred to themselves as princes fought for supremacy and to be the guardians of the monarchs that had just been confined to the Gondarine castle in the town of Gondar. Since the monarchs were considered sacred and ordained by the order of God, the lords did not have the courage to claim the throne. The wars fought among them had sometimes taken ethnic lines between Oromo, Tigray, Amhara and Agew.

While Ethiopia was busy with its internal wars in the 19th century, the slave trade from Africa was substituted by colonialism by European powers. The substitution did not help improve the life conditions of Africans. Rather it created first and second class citizens and subjugated Africans to Europeans.

The Berlin Conference of 1884 gave the modalities on how to partition Africa to each colonial power.

As part of its share in the Berlin Conference, Italy has attempted to colonise Ethiopia in 1896. However, Ethiopia successfully defeated Italy at the Battle of Adwa. Many Africans and Latin American and Asian people have taken the Victory of Adwa as a symbol of independence, liberty and equality especially against Europeans and white colonialists. Italy went home empty handed without being able to succeed what it came to fight for.

Internally, right after the Victory of Adwa, the then Emperor of Ethiopia saw the encroachments being made by colonialists to the surrounding borders and decided to expand the area of the Empire by amalgamating the smaller but several nationalities in the region. Many conquests were made to the South, South Western and South Eastern parts of the Empire. That is how the current malty-national Ethiopian state has been formed.

In the wake of the 20th Century, European superpowers of the time were approaching the then emperor (Lij Iyasu) to have him on their side in their fight to strive once again to conquer Ethiopia. Being of a mixed origin on one hand from a Muslim convert Oromo father and a Christian Amhara mother, Lij Iyasu made himself busy amalgamating forces from peripheral areas, notably Muslim regions such as Harar, Djibouti and Somali, hedging the central throne.

He was not liked by the aristocrats of the central government due to his alleged advocacy of Islam, leading to his imprisonment and later demise. He is credited wiyh having attempted to modernize Ethiopian politics by including peripheral warlords in the politics of the central government.

In his place came Teferi Mekonnen, one of the cousins of Emperor Menilik II, later crowned as Emperor Haile Sellasie II. Emperor Haile Sellasie issued the first ever Constitution to the Empire in 1931. While the Constitution could be admired since it was the first ever move by an Emperor to be issued to his people, it was highly limited in scope and rather gave a written mandate of the subjugation of the mass of the people under the Kingdom.

Some historians argue that the Constitution was issued as a matter of the fact that it was a prerequisite in order to join the League of Nations. It did not have any room to answer questions of human, democratic and equal participation rights, both economic and political rights. Therefore, it had no energy to address the looming national question of the time.

Before any revision or amendment was sought, the 2nd Italia-Ethiopian War was fought ensuring the occupation of Ethiopia by Italy in 1935. This was the continuation of Italy’s attempt to colonise Ethiopia.

Italy has temporarily succeeded in causing the Emperor to make a strategic retreat from the first battle, the Battle of Maichew and the battle in the capital Addis Ababa, to migrate to England seeking help from the League of Nations.

Ethiopia had to endure Italy’s conquest for the next 5 years, albeit with a lot of resistance from patriotic forces in different parts of the country. The effort of Italy to found a colony in Ethiopia could not last any more than 5 years and it was defeated in 1941.

During this time, as was prevalent in any other colonies, no human rights, democratic or nationality questions were answered. Italy was rather busy dividing the public at large into smaller ethnic groups and religious factions for divide and rule.

After the defeat of Italy in 1941, the Emperor returned back and started building a ransacked nation from several insurgencies and wars. He issued another Constitution, the 2nd constitution, in 1955.

This was a much awaited one especially by the intelligentsia as they were expecting to see a Constitution that resembled the ones in the likes of England, Belgium, Spain and most of Scandinavian countries where the majority of them were educated.

To the dismay of them and the entire Ethiopian people, the Constitution but recognized the Emperor as the only rightful owner of the land, the waters and the people. That meant that it was still an absolute monarchy instead of the much-sought constitutional monarchy.

Concurrently, the situation of Eritrea had exacerbated the problem of Ethiopian politics. Historically, Eritrea was always the most northern part of Ethiopia for ages. Many historical accounts describe parts of the current Eritrea as being governed by the Ethiopian Emperors.

Thus, it shares the ancient and medieval history of Ethiopia as Medr Bahri – literally translated as – Land of the Sea. Of course, it will be worthwhile to mention that some foreign powers had controlled some parts, especially the coastal areas of Eritrea in different times, notable among them the Ottoman Turks and the Egyptians.

However, in the 2nd half of the 19th century, Italians settled in the coastal areas and mainly the Assab area of Eritrea since 1882 as part of their plan to colonise the whole of Ethiopia. The formal colony of Eritrea was created in 1890.

The Emperors of the time could not immediately defend Eritrea from Italian invasion due to various reasons but mainly because of lack of arms and rations among others. Thus, the Medr Bahri province of Ethiopia had been taken by Italians as a colony while the rest remained as independent Ethiopia.

When the Italians were defeated by joint forces of Ethiopia and British East Africa in 1941, they left Eritrea and the Imperial British forces were allowed to become regent administrators of Eritrea for the next 10 years. In 1951, Eritrea became a confederate of Ethiopia under UN Resolution. Nonetheless, in 1962, the Emperor decided to unilaterally to dissolve the Eritrean parliament and reclaimed the territory of Eritrea as part of a unitary Ethiopia.

This action of the Emperor caused a great deal of disappointment and resentment among the Eritrean people, especially the elites. They were not happy about the dissolution of the federation given that they had not been consulted by the Emperor.

As a result, factions of movements for independence started to proliferate especially in the lowlands of Eritrea. The Eritrean Liberation Movement (ELM) and the Eritrean Liberation Front (ELF) started in 1958 and 1961 respectively as liberation movements. The War for independence followed for the next 30 consecutive years until Eritrea won its independence from Ethiopia in 1993.

The Emperor’s inaction to modernize Ethiopian politics toward creating a state in which all individuals and groups enjoy their democratic and human rights coupled with the agenda of the world superpowers toward the Horn of Africa had given birth to what was known as the Student Movement.

University students in Ethiopia and those that were pursuing their studies in Europe and USA sought for a reform in the imperial system. The movement had also infiltrated senior students in some high schools in Addis Ababa and some other towns. The National Question in Ethiopia has been flagged since then as part and parcel of the student movement with a clear ideological and political line of debate.

Notable among these lines was a line pursued by Walelign Mekonnen, a member of the perceived dominant nation and a university student at the end of 1960s. He wrote a controversial and yet still debated article regarding what he referred to as “The Question of Nationalities [of Ethiopia]”.

He wrote, “The Socialist forces in the student movement till now have found it very risky and inconvenient to bring into the open certain fundamental questions because of their fear of being misunderstood. One of the delicate issues which have not yet been resolved up to now is the Question of Nationalities-some people call it ridiculously tribalism-but I prefer to call it nationalism. Panel discussions, articles in STRUGGLE [magazine] and occasional speakers, clandestine leaflets and even tete-a-tete groups have not really delved into it seriously.”

He further asks, “What are the Ethiopian peoples composed of? I stress on the word peoples because sociologically speaking at this stage Ethiopia is not really one nation. It is made up of a dozen nationalities with their own languages, ways of dressing, history, social organisation and territorial entity. And what else is a nation? Is it not made of a people with a particular tongue, particular ways of dressing, particular history, and particular social and economic organisation? Then may I conclude that in Ethiopia there is the Oromo Nation, the Tigrai Nation, the Amhara Nation, the Gurage Nation, the Sidama Nation, the Wellamo [now Wolayta] Nation, the Adere [now Harari] Nation, and however much you may not like it, the Somali Nation.”[1]

Such an article has become the basis upon which the debate on the national question for almost all of the political struggles in Ethiopia has openly been pursued. Until 1974, when the Imperial regime was toppled by a junior military junta known as Derg (which means committee), there were no organised political parties albeit the existence of the unorganized movements we have mentioned above.

Organized political parties started to mushroom only right after the Derg took power. The Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Party (EPRP), All Ethiopian Socialist Movement (AESM), ‘Proletariat League’, ‘Revolutionary Fire’, ‘Ethiopian Oppressed People’s Revolutionary Struggle’ lined up to cooperate with the reigning military regime especially in the early days of its reign. They formed a tactical alliance called Ethiopian Marxist Leninist Democratic Union although it did not last long.

The National Question in Ethiopia comes amid all these issues. In the north, following the dissolution of the federation, some groups that had not been pleased with the decision of the Emperor started the struggle for independence as mentioned earlier. They considered the Ethiopian government as a colonialist over Eritrea. This is the first and probably the only struggle that considered a black country as a colonialist that must be decolonised from.

In the neighbouring Tigray region, another wave of struggle for forming an independent communist state started through Tigray Nations Progressive Association, Tigray Peoples Liberation Struggle and Tigray Peoples Liberation Front (TPLF). In the east, groups from the people of the mainly Ogaden clan and other Somali speaking clans started another struggle through the Ogaden National Liberation Front (ONLF) to secede the Somali-Nation from Ethiopia and join greater Somalia.

In the south and west, some forces from the Oromo ethnic group were fighting for independence from Ethiopia through mainly the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF). Also, there were scores of struggle for equality and justice in parts of southern and south western Ethiopia mainly among Agnua, Berta, Sidama and ethnic groups from the Rift Valley region through the Gambella People’s Liberation Movement, Berta People’s Liberation Movement, the Sidama Liberation Movement (SLM) and the Rift Valley People’s Liberation Movement etc… To the surprise of many almost all political parties and armed liberation movements were led by a far left ideological orientation.

In parts of the north western and central eastern regions of the country, a pan- Ethiopian armed struggle called the Ethiopian People’s Democratic Movement (EPDM) was active. This was the only struggle that included people of various ethnic backgrounds.

As the student movement was the core of the ideological leadership, a portion of the students’ movement believed that the national question was the key question and should be resolved as part of the socialist right of self-determination up to secession to form their own states.

The other portion heavily criticized the former as being narrow nationalists and that the key question in Ethiopia is associated with class interactions and therefore the national question should be addressed within the framework of the class struggle.

Even though it is minority by the time, the third group was advocating the liberal approach to the question and emphasized that if individual rights are observed in a truly democratic system, without any further struggle and political discourse the national questions could get resolution.

As everybody can see from the political history of Ethiopia, an intensification of national question which is laden with violent conflicts and armed struggle arose basically when capitalism started to grow in the womb of feudalism.

In due time, the [Derg] military regime continued to escalate suppression of dissent, freedom of association and freedom of speech. The main political struggles changed tactics to become clandestine, guerrilla fights, armed struggles and movements taking place outside of the country. On the other hand, the regime had two pressing questions to answer – the question of land ownership and the question of nations and nationalities.

On the question of land, the regime issued a proclamation right after taking power giving privilege of ‘land to the tiller’ following some examples of the then South and North Vietnam along with some modifications.

As regards to the question of nationalities, in the beginning it denied that there was a genuine national question from the fear that advocacy on the national question would lead the country to irreversible disintegration and undermine unity of the country.

But when the resistance movements and armed struggles intensified, the regime was forced to form what was known as the ‘Institute of Nationalities ‘composed of notable scholars from various backgrounds and disciplines. The institute was tasked to answer the questions of nations and nationalities in Ethiopia. The scholars had done extensive research on almost each and every nationality and ethnic group existing in Ethiopia and presented their findings to the regime.

Their general conclusion was that there was no group to be qualified and recognised as a nation.

Following the conclusion by the members of the Institute for Studies of Ethiopian Nationalities, a census was executed for the first time ever in the history of the country and the third Constitution was drafted and made available for discussion and an eventual referendum.

The results of the referendum resulted in what is known in history as the People’s Democratic Republic of Ethiopia (PDRE). Regional administrations were divided along geographic dispersions. Some of the regional administrations managed to get a self-administration status. But this was a complete socialist exercise therefore effectively eliminated the possibilities of democratic participation and opposition voices being heard.

Nevertheless, the coercive and repressive exercise of the regime could not last longer than half a decade.

The armed struggles led by the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) won the struggle for power and founded a provisional and later a transitional government.

The transitional government was composed of the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF), which by itself was formed by a coalition of the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), the Ethiopian People’s Democratic Movement (EPDM), the Oromo People’s Democratic Organization (OPDO) and a front of other numerous political parties representing several nationalities and ethnic groups in the South, Southwest and Southeast.

The question of Eritrea was addressed by a referendum held under the observation of the UN. A majority of the Eritrean people demanded secession from Ethiopia. As for the remaining Ethiopia, a new Constitution was drafted. This Constitution is the fourth in the contemporary history of Ethiopia.

Because of many similarities to Ethiopia, I will briefly deal with the national question in our continent’s most populous country, Nigeria. Arua Christopher has eloquently expressed this in one paragraph. He said the national question in Nigeria persists because of the problem of lack of an evolving political structure that would accommodate the interests of all the various nationalities which now constitute the Nigerian nation, starting since independence.

Ninety seven years after the first Constitution was drafted in 1922 and several other Constitutions since independence on October 1960, Nigeria is still battling for a workable structure to take over from the one which has been severely weakened by the protracted failure to resolve the national question.

Given the similarities and specificities on National Question of the two most populous nations on our continent, Nigeria and Ethiopia, what should we do to address this sensitive and existential question?

In my humble opinion, the first thing we need to do is to accept the fact that many of the African countries are multi-national states and must therefore work with that knowledge.

The national question is a real question. I would be the first to admit that even that is not easy because we have people who consider our differences irrelevant and claim that we are a monolithic and homogenous entity, which is not true.

Our unity should not be based on a lie, a denial of the many selves we have and we love. So we do need to recognize that and work on that truth.

Once we acknowledge our diversity, we will have a better view of how difficult democratisation can be for us than the average relatively homogenous post-industrial country in Europe. Theory, especially western theory and literature, is not on our side.

Most political scientists tell us that it is extremely difficult for countries with a heterogeneous demography to establish and sustain a democracy. Even experience is not on our side. As some of you who follow Ethiopian politics closely, would already be thinking, I would be a hypocrite if I said balancing the demands of ethnic nationalists and pan-Ethiopian nationalists is an easy ride. It is not a bed of roses. It is extremely complicated and if not managed well, perilous. International conflicts are potentially dangerous and as seen in my own country and in majority of African countries, as inherently violence.

In my country for example, this beautiful, massive, tri-coloured ship we call Ethiopia is being rocked left and right by the bipolar ethnic and pan-Ethiopian tides of nationalism. The way to steady the ship cannot be letting one tide win, because if you allow one tide to pull or push all the way, you will risk capsizing the ship and you will have no ship to even pull or push or rock anymore.

The only way you can right and steady a listing ship is by maintaining the right balance. It is in difficult times like these that ships actually need highly skilled, disciplined and level-headed captains. In quiet waters, anybody can steer the ship to its destination, but in difficult times you need real captains. We, the leaders, are the captains of our nations.

Wwe have the responsibility to constantly watch the tendencies of those tides and maintain the balance of our ship accordingly. And I dare to believe, just like our pan-African fathers and mothers believed 66 years ago, that, with the right leadership, with the right captain-ship, we can overcome these tides.

We can overcome these turbulent times. And I dare to believe because I know that despite our differences, our destinies are still tied together and our people know that more than we realise because it does not often show in our newsfeeds. We only see it when we are tested.

It would be remiss of me if I did not mention here the overwhelming sense of togetherness we, Ethiopians, we Africans, demonstrated when our aircraft crashed on March 10 this year just outside Addis Ababa. All our internal bickering and hatred stopped and in its place grew a sense of togetherness some people thought we had long lost. Nobody asked for it. I did not ask for it. It just happened. It’s as if our dialectical tides agreed to have a time out – a time out that they needed to bring their voices together to ask for justice for those whom we lost, a time out they needed to right the wrong of western media representation of the incident, a time out they needed to console the bereaved – together as one big family.

No force, no office of government could have called for that togetherness that effectively. It was successful because it was organic, based on the ideal that out of many we are one, diverse yet one nonetheless.

That is why I dare to believe that it’s possible. That is why I believe that our unity shall not come at the expense of our diversity and that our diversity shall not necessarily threaten our unity. I propose to you today that unity and diversity are not and should not be an either-or proposition.

Our people should not be forced to choose between celebrating their diverse cultural heritages and signing up to larger national and continental visions. With the right indigenous, home-grown leadership, with the right home-grown captainship, I believe we can and we must strike the right balance and steady our ship.

So let us recognize our diversity. Let us embrace it. Let us identify where each can compliment and enable the other and let us harness those strengths to our advantage. We have done it before and we can do it again.

Please allow me tell you a very brief story here from a chronicle of the Battle of Adwa, the battle at which my fathers and mothers, your fathers and mothers, beat European colonial powers and cemented their independence, the battle of which my brother President Mbeki often talks very fondly and very eloquently.

At that Battle, there was a moment when Ras Alula, one of our generals of Tigrayan origin, which is from the north, noticed that the two Italian generals were fighting from two different hills and in between them there was a sort of a valley. The idea was that if one was to be attacked badly by the Ethiopian warriors, the other was within a reasonable distance to come to his rescue.

When Ras Alula noticed that, he immediately sent a message to our Emperor Menelik II advising that those two Italian forces must not be allowed to communicate or assist each other. And the only way we could accomplish that, he said, was if we cut them in the middle by taking the valley and cutting their line of contact.

Emperor Menelik, an Amhara who hails from the central highlands of Ethiopia, heeded the advice of this patriot. And even if Menelik II was the overall mastermind of the battle plans, he recognized the undeniable warfare experience of his general. He also understood that because Ras Alula was from the area where the battle was taking place, his local topographical insights could only be very useful. So he made the decision to act swiftly on the advice and control the valley and cut the Italians into two.

That had to be done fast. So he picked the Oromo warriors, from the south central, who were renowned for their exceptional horse riding skills. And before the Italian generals even got a chance to warn each other of what was coming at them, the Oromo cavalry overwhelmed the valley on the back of their horses and cut the supply and communication lines.

The only thing the Italian generals could do then was hastily to retreat to save their lives. In this one moment that did not take more than an hour – from planning to execution – you can see the local, topographical knowledge of a northern Ethiopian, the humble but cunning leadership of a central Ethiopian and the horse riding skills of the south-central coming together to save the sovereignty of our country.

That is why I dare believe that our diversity, our multi-nationality is not necessarily a threat to our unity, to our peace and to our prosperity. It just makes the sailing rather patchy and difficult. But with the right captains, we can not only navigate around it but we can even use the wind, as sailors do, to propel us forward.

I will take a few minutes to show what Nigeria and Ethiopia should do to address the existing national questions.

First of all the intellectual and business elites of these countries, drawn from the various nations or nationalities should not mistake their class aspirations for a greater share of state power and prestige and greater business access for accumulation, as the interest of the nations and nationalities to which they belong.

This kind of opportunist solution hampers the programme of fundamental social change that should be designed for the people. The structural solution we design should solely take the people’s interests first.

Secondly, since mainstream politics in our continent has proved incapable of solving the contemporary national question, this is true both in Nigeria and Ethiopia, it is suggested that an active, organised and peaceful civic movement is something which should be instituted. This would help to mobilize citizens not only in the politics of genuine and participatory democratic dispensations but also foster social changes in terms of accelerated inclusive and shared economic growth and development.

We should not delegate this issue to political and business elites for they would focus on their class interests rather than the interests of the masses.

The pursuit of nationalist objectives can take many possible forms – ethnic nationalism, cultural, religious nationalism, liberal nationalism, civic nationalism – too many to list here. What we find prevailing or contesting for attention and relevance in most of our countries is ethnic nationalism probably because it is easier to mobilise people along ethnic lines than along ideological lines, for example.

But it is not all doom and gloom. Ethnic mobilisation, despite its many criticisms, has good potential, too. We can use it to mobilise social capital and inspire collective action. As you know, most of our countries still have a huge chunk of our populations in poverty.

One of the concomitant effects of poverty is a substantial reduction in social capital as people scramble for limited resources. This gap can be compensated for by using ethnic nationalism to bring people together to build that social capital.

The second potential is its utility in mobilising collective action. Again, unfortunately, not all of us are inherently inclined to act for the collective good. And with the rise and expansion of capitalism, industrialisation and globalisation, our African social instincts are being replaced by individualism. That individualistic predisposition can be compensated for by the collective action that follows collective identity, which is at the centre of ethnic nationalism.

So, ethnic nationalism is not without pros. But it has to be managed very carefully. As seen in Ethiopia and elsewhere, extremist ethno-nationalism from both far-right and far-left are dangerous not only for the other side but also affect negatively the nation which generates it.

If we entertain it too much we can risk breaking the nation into pieces as every ethnic group begins to declare that its interests can only be respected in an autonomous state. People can also become less tolerant, developing dichotomies of “them” and “us”, “the indigenous” and “the comers”; “the natives” and “the non-natives”.

What ethnic nationalists often overlook is that identities are multiple and also socio-historic constructs. That means they are not fixed. Identities are not completely primordial and can shift. Who we are is not explained by our ethnicity or language alone. Our gender, ideology, religion, socio-economic class all contribute to our sense of who we are and they shape the way we view and interact with each other and with the world every single day. They inform our will.

Each one of us is made up of multiple identities and we cannot choose for others which one they should put at the top of the pecking order of their multiple identities. To some people it is their gender. To others it is their religion. To others still, it is their ideology. Ethnic nationalism risks flattening all this multiplicity of identities into one primordial feature defining who we are, but which we did not choose.

The liberal nationalist Ernest Renan told us, as far back as 1882, that “there is something in man which is superior to language, namely, “the will.” The will to live together. And I tell you, today, that there is something in a man, in a woman, which is superior to not only language, but also ethnicity, ideology, race, religion, namely the will.

The will to live together, regardless of your differences. I submit that challenge to you today. Are you willing to take up that will not only to co-exist but to live and thrive together even with people that do not necessarily speak your language, people that do not necessarily have your complexion, people that do not necessarily share your world view?

If that is what moving ahead takes, if taking up the will is what getting ahead as South Africa, as Tunisia, as Somalia, as Senegal, as Madagascar takes, are you willing to look past those few things that separate you and embrace the many that unite you? Are you ready?

Democracy, inclusiveness and tolerance make a positive environment for a successful regulation of international disputes. As seen in my country in recent history, violent, forceful and unilateral imposition of solutions only worsens the situation. The unresolved and undecided lingering national question significantly aggravates the consolidation of democracy.

I often get asked why Ethiopia was never colonised, how Ethiopia managed to overcome the assault of a modern European nation with superior firepower. Is it because we were necessarily any more patriotic than our less fortunate neighbours? Not at all. We are all patriots on this continent. My answer is simple. It was because our forefathers and foremothers had the will – the will to put their internal differences aside for a moment and face the pending, bigger danger called colonization together. Identifying that will as a source of strength and using it to unite the nation, of course, took centuries-long statehood and astute leadership, a sort of leadership our countries need today – but for a different fight.

Today, brothers and sisters, the pending danger for a lot of Africans is lack of peace and lack of economic opportunities. And those two go hand in hand. It is becoming increasingly difficult for countries that are not politically stable to attract foreign direct investment, tourism and cross border trade all of which could have contributed to creating jobs for our increasingly young population.

I recently heard a shocking statistic, which needs qualification, that about 40 percent of African young people who joined extremist groups cited lack of jobs and deaf ears from their own leaders, as a reason for joining the extremist groups.

Note the viciousness of the cycle here: young people say lack of jobs and lack of good governance is leading them to extremism and violence. We, leaders and governments, say that the violence and extremism is chasing away domestic and foreign investors and tourism, and, hence, job opportunities. It is a vicious cycle that needs to be broken.

And I propose that we can do that by adopting a more inclusive civic nationalism that can bring about peace, positive competitiveness and prosperity, a sort of nationalism in which we weigh, value and incentivise each individual – be it an ordinary citizen or a politician – based on his or her merits not their ethnic identity, with due emphasis given to the marginalised sections of the society.

So to tie up what I said above, I urged the people, the citizens, to look past their ethnicity when they think of who they are, when they think of their citizenship, when they think of their place in society and as they go about their daily lives. Now what must we do, as leaders, as governments, as political parties, as civil society activists and elites in how we relate with our electorates to promote the meritocracy I spoke of just a moment ago?

Political scientists have developed a typology of the ways in which politicians relate to citizens. They call them linkages. The first is clientelistic linkage. The second is charismatic linkage. The third is programmatic linkage.

Clientelistic linkage is sectarian and exclusive. It assumes a base whose interests we have to regard and serve above everyone else’s because that base is the one we will fall back on in case something goes wrong. They are the ones whose votes we count on come the next elections. They are the ones we will go to and hide in if some miraculous power pushes us over from our perch and justice is due to arrive.

Clientelistic linkage perverts accountability. More than anything, it divides the country in to different tiers of citizenship – first-class citizens (our clients) and then second-class citizens, which is everyone else. Equality will never be achieved under this linkage because even if someone else from another base takes power, she or he, too, will have her or his base. And the tier of citizenship does not disappear; it just shifts. That has not taken us anywhere and it will not take us anywhere in the future.

The second one is charismatic linkage. In this sort of relationship, the politicians and the citizens are linked via one or through a few charismatic leaders that the people somehow trust to have the country’s best interest at heart. We have had quite a few of these well-intentioned, charismatic leaders in Africa. The problem with this kind of linkage is that no leader can ever be a substitute for robust institutions.

While the leaders may indeed have had great intentions, in the absence of institutions, the country would not have anything to fall back on in cases of emergency such as the sudden passing away or resignation of that charismatic leader who had carried the basket with all our eggs in it.

The sort of linkage I recommend for Africa is the programmatic one. Under the programmatic linkage, politicians will make measurable, time-bound promises to their electorates. They lay out clearly defined visions and policy priorities. The electorates weigh the relevance of those promises and policy priorities against their personal and collective priorities and make a decision peacefully. But they do not cut the leaders a carte blanche.

If the politicians depart from those promises and policy priorities, the citizens will whip them back into track by reminding them of the promises they made. The free press plays a big role in this. If the politicians do not deliver on their promises even after the reminders, then the next election will provide the people with another peaceful chance to vote them out and replace them with a more able leadership.

Nobody will cover for their failures because their failures and successes can be clearly and objectively measured against their promises.

Now let us connect the dots. Luckily programmatic linkage works best with civic nationalism, of which I spoke briefly at the beginning. Now I am tying civic nationalism as my recommended form of nationalism and programmatic linkage as my recommended form of citizen-politician linkage.

Under the merit based civic nationalism and programmatic linkage, citizens will only judge politicians solely and objectively on the merit of their work. A 23-year-old young woman may judge a candidate or a party on the basis of his or her commitment towards inclusive and equitable share of the countries resources, balanced economic opportunities, green economy, gender equality or free education etc.

A 23-year-old young man may prefer to vote for a candidate or a party that has freedom of the press, a pan-African foreign policy, and liberal economic policies at the top of his or her agenda. A 60-year old man or woman may prefer a party that works for equal observation of individual and group rights including the rights of nations and nationalities.

The beauty of this system which brings together civic nationalism and programmatic linkage, of course with due emphasis given to the rights of minorities and marginalised groups, between politicians and citizens is not only that it allows for more accountability but also that it allows for the fostering of strong institutions without which the candidate or the party will never achieve the goals she or it sets out to achieve.

I believe this is how we can achieve solutions to the burning quests in our continent, including the national question, in a democratic and peaceful manner.

I thank you for your kind attention.

[By decision of the then Organisation of African Unity, Africa Day falls on 25 May. This 2019 Africa Day Lecture was delivered on 24 May because this year Mr Cyril Ramaphosa was inaugurated as President of the Republic of South Africa on the actual Africa Day, 25 May, 2019.] (1)

[1] Walleligne Mekonnen, a fourth year student in the Faculty of Arts, PSIR in 1969, and was published on STRUGGLE[ Vol. V, No. 2, November 17, 1969] by the University Students’ Union of Addis Ababa ( USUAA).